In the summer of 1964 Jarman embarked upon his first journey to America, from July until the end of September. After a stay in New York he travelled on to Canada to visit his friend Ron, whom he had met in London. Many of the poems later published in A Finger in the Fishes Mouth were written at this time. As Jarman repeatedly emphasises in his autobiographical writings,87 his first journey to America and the impressions and encounters associated with it provided a decisive impulse for his consciously realised coming out and his wish for a more liberated and self-determined life.

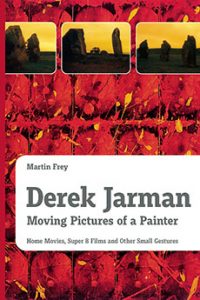

David Hockney at the Picasso exhibition

Having returned to London after his first, three-month stay in America, Jarman encountered David Hockney at a Picasso exhibition in the Tate Gallery: ‘In the autumn of 1964, Ossie Clarke and I visited the Picasso Show at the Tate and collided with David straight off the plane from L.A. He invited us back to his freezing flat for tea and we climbed into his bed to keep warm as he unpacked his suitcase full of bright fluorescent socks and underwear and the first Physique Pictorials I had ever seen.’88

Jarman subsequently got to know Hockney better and became a part of his closer circle of friends around Ossie Clarke and Patrick Procktor – whose role he would play years later in Stephen Frear’s film Prick up Your Ears (UK, 1987) – and in this way he met numerous young contemporary artists from the London and international scenes. The period of isolation, seclusion and loneliness seemed to be at an end. In the second half of the sixties an increasingly freer life became possible, one that could be shaped counter to a public sphere that continued to remain repressive: ‘Through David and his friend Patrick Procktor I met all the young painters; this changed my life. There were shows and parties and nights on the town; we all fell in and out of each other’s beds. It was enriching. Sex was bonding, pedagogic, a way of learning.’89

The primary focus in Hockney’s work

As a painter in the United Kingdom of the sixties, Hockney was not only among the first to break a societal taboo still seen as absolute at that time, by publicly affirming his homosexuality – in addition he had also begun to directly, unambiguously and straightforwardly thematise homosexuality in his works. The primary focus in Hockney’s work is not on styles and techniques of working but on his life and lifestyle, which are repeatedly present in his work, occupy the centre of attention and also appeared to Jarman as something of not insignificant importance. Hockney’s statements, which were extraordinarily courageous at that time, provided a model for a whole generation. In this context this model is to be attributed an essential and integrative function in the achievement of both a personal and a general, societal self-concept – not only for Hockney himself but also for those artists and friends that he gathered around him. (…)

An essay on Hockney

In an essay on Hockney, Jarman describes how, for example, a

superficiality like Hockney’s dyed-blond hair – which seems so unexceptionable and commonplace from today’s perspective – broke the strict conventions of masculine appearance in the sixties: ‘When David dyed his hair blonde, he lit up more than his bathroom mirror. It seems such a small gesture now but then it broke every convention of the ghastly fifties. The grey suits and black shoes, stiff collars and ties, the tight furled umbrellas of the middle classes barely ruffled by the wind of change, a fucked up closet culture where queers were bashed in the tabloids.’91

Hockney’s work

Hockney’s works are autobiographical, their themes are directly connected with him, his sexuality and the environment of his private life. As reserved or cryptic as some of the very early works may appear from today’s perspective, even many of them already thematise homosexuality as their subject in a direct and immediate form that was new, ‘shocking’ and ‘scandalous’ for that period. In the early sixties, while a student at London’s Royal College of Art, he created an initial series of so-called ‘coming out’ paintings, including a portrait of Walt Whitman, to whom references can also repeatedly be found in other works. The well-known painting We Two Boys Together Clinging was created in 1961: two embracing men can be recognised in it and the phrase of its title, the first line from Whitman’s ‘Calamus Poem No. 26’, has been inscribed into it. Hockney’s painting Adhesiveness (1960) also makes reference to a term used by Whitman, with which he tries to give a name to close friendships between men.92

Ford Madox Brown’s painting

In another student project created in 1961 at the Royal College of Art, Hockney also occupied himself with Ford Madox Brown’s painting The Last of England. He inserts an entirely personal narrative into his ‘copy’ of the painting – which he has renamed into the questioning The Last of England? – by putting himself in the place of Brown and his heart-throb Cliff Richard in the place of Brown’s wife (see fig. 17). In his biography of Hockney, Peter Webb explains the background behind this work:

Cliff Richard

‘At the Royal College, students were set the project of copying a famous painting and Hockney chose Brown’s The Last of England. He rejected the pathos of the original as well as its sharp focus. Instead, he depicted himself (labelled 4.8 in his alphabetical code which equalled D.H.) with his arm round his fantasy lover, Cliff Richard (D.B. for Doll Boy). However, he kept Brown’s circular format and added the title made into a question: “The Last of England? Transcribed by David Hockney 1961”. […]

Doll Boy

‘Hockney has borrowed the schoolboy code of one of his favourite poets, the homosexual Walt Whitman, in which 1=A, 2=B and so on. Thus 3.18=C.R., which identifies the figure as the singer Cliff Richard. Hockney was at this time infatuated with Cliff Richard and had decorated his studio cubicle with photographs of the singer whose current hit record was entitled “Living Doll”. The song was about a girl, but David changed the sexual roles and made Cliff his “Doll Boy” [also the title of a painting of 1960], the object of his love and at the same time his chosen symbol of sexual repression.’93

Private themes

Private themes become more and more dominant motifs in his work: Hockney’s friends, his long-time partner Peter Schlesinger, his family, the boys around the pools of America’s West Coast, his travels, his ‘daily life’ can be seen in many of his paintings. In Jarman’s words: ‘He chased the shadows from his work, the shadows that hide our lives.’94 Hockney now deliberately ignored traditional taboos and thematised corporality and gay sexuality in his works in a way that gradually became more and more immediate and direct.

Cavafy etchings

In the mid-sixties he created the series of the so-called Cavafy etchings as illustrations of poems by the Greek writer Constantine P. Cavafy. This series visualises Hockney’s personal and extremely intimate impressions in a naturalism that was directly provocative at the time: in its aesthetic disinterest it no longer seeks to beautify, conceal or euphemise anything. The studies of nudes and the recorded scenarios resist almost any idealisation in a classical sense. Like snapshots they seem to approach towards realistically accurate images and to suggest an everyday and commonplace quality. Jarman presents them as diametrically opposed to the idealised figures of Jean Cocteau:

Jean Cocteau

‘When I saw David Hockney’s Cavafy etchings of very ordinary young men in bed together, they were something quite new; if you look at Cocteau’s boys, they were idealised; these were very honest. David was honest to the point of naïvety.’95 In the first half of the sixties Hockney became one of the first to unreservedly and radically turn his back on romanticising motifs used to serve as alibis. He tore away the veil of masks and ambiguously interpretable suggestiveness by rejecting the available store of stereotypical, mythological or antique motifs and drawing the content of his works out of his personal, lived present.

The late sixties

Even in the late sixties and in both photography and the other visual arts, openly thematising and depicting male sexuality, nude male bodies and corporality – not to mention homosexual connotations, content and themes – were almost exclusively relegated to the level of metaphor and could be expressed almost exclusively by this indirect means. The idealisation of the perfect, strong and active male body was still omnipresent at that time, both in photography and the other visual arts.

Classical motifs and their ideals

The content of these representations could never be permitted to draw too close to the reality of the present, let alone permit direct associations with the individual realities of their viewers’ lives. Stretching back for decades and centuries themes had been based on classical motifs and their ideals, and mythological subjects or themes from Roman or Greek antiquity were repeatedly utilised to provide pretexts to permit the depiction of the nude, active or battling male body. Concerned to achieve a more or less correct classical contrapposto attitude, poses were staged, surrounded with fake Doric columns or other stereotypical antique props. The thematic sequences of romantic bathing youths, of sailors in Cocteau’s and others’ prior works and of fighting, wrestling, swimming, hunting and heroically posing men can be continued almost indefinitely.

© Martin Frey: Derek Jarman – Moving Pictures of a Painter. p. 69 – 72